Mangahao Works Tragedy

Published on June 22, 2022

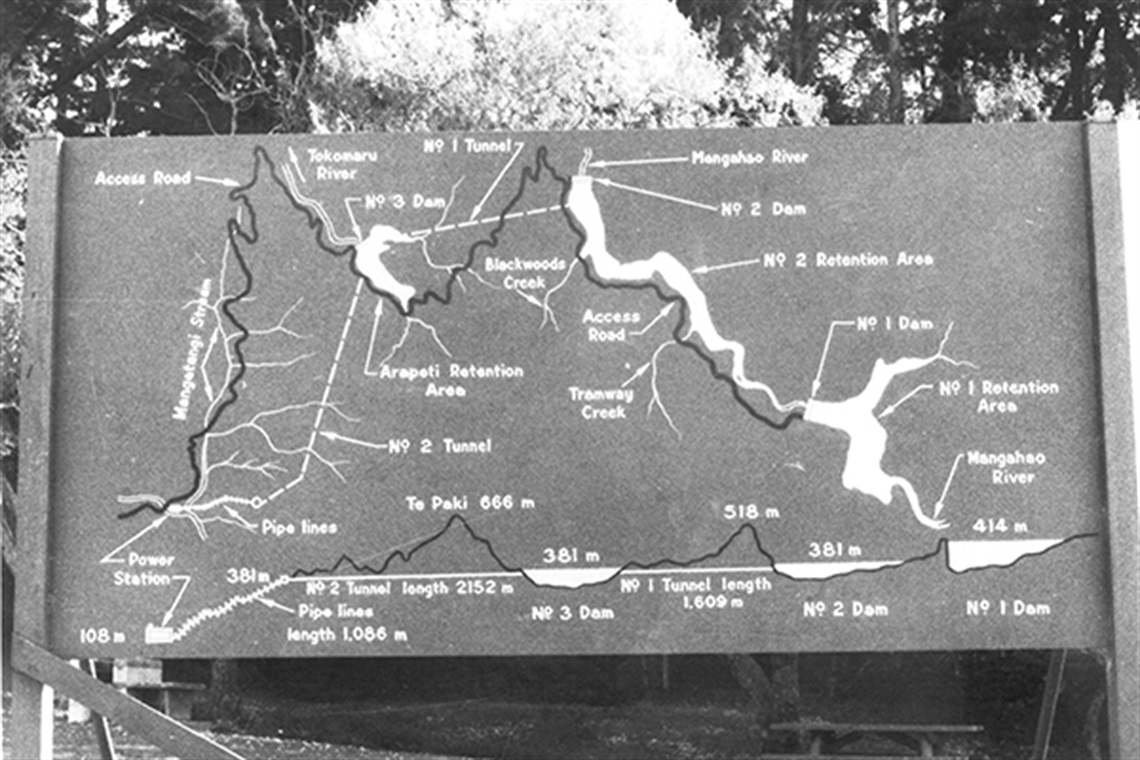

This year marks 100 years since the Mangahao Tunnel tragedy. Seven men lost their lives to carbon monoxide poisoning when ventilation systems failed during the construction of Arapeti in July 1922. Digitised in Kete Horowhenua, Bob Ayson’s Book ‘Power in the Hills’ describes how the disaster unfolded.

From: Bob Ayson’s book Power in the Hills – digitised in Kete Horowhenua:

STRIKE!

1922. The year kicked off with a major problem at Mangahao. It was caused by a Government national retrenchment programme with a reduction in the rate of pay for all PWD employees. Although the outside workers’ accepted a cut of from 15s to 14s a day, the tunnellers, who had received 32s to 38s per day, refused to accept a proportionate reduction, downed tools and went on strike. This was on February 4. Those who had fixed contracts were being reduced by 1s per day per man. Coates, the Minister of PWD, said he was willing to listen to their side of the case which he described as a ‘temporary disagreement’.

But the tunnellers’ didn’t see it that way. A contract was a contract and it shouldn’t be altered at the whim of the department. Besides, the tunnels they were driving was through very hard country and it took an average of drilling 20 to 23 holes to bring out the face. As the explosives were paid for out of their contract money, and the sharpening of the drill bits, this was already a costly reduction. Despite this, the tunnels were being put through cheaper than any other tunnels ever driven in New Zealand.

In addition, the men found it totally unacceptable to be told to go back to work, without offering their own proposals. This was not what they wanted to hear and many packed up and left the works. Their 16 points proposal was submitted to the Minister when he attended a meeting at Mangahao on February 15. They told him they were prepared to accept the reduction provided the department considered their proposals which included reducing the price of explosives from £6 to £4 a box and to halve the charge for sharpening the drill bits.

But the Minister said he could not accept that arrangement as it would be too costly to dig the tunnels. He offered instead, a straight contract instead of a cooperative contract. This caused a dead-lock in negotiations and the men were adamant that unless their ‘reasonable demands’ were met ‘the work will be at a standstill for a hundred years’.

The tunnels were at a standstill until April. Then in desperation the PWD offered the men contracts by tender to complete the tunnels. Six parties of tunnellers took up separate contracts at less than the price per foot than under the old contract. But if they increased their pace, they could make more money under the new contract. Work started on both tunnels again and good progress was being made, until disaster struck.

Night of tragedy

One hour before midnight on Sunday July 2, the No 2 tunnel mouth, at the Arapeti end, loomed, dark, forbidding and silent as the grave. The tunnel had been driven in 30 chains, and near the face, about 27 chains, a petrol engine pumped out the water which poured through the tops and sides of the tunnel, in a never ending stream.

The pump’s fumes were removed by an electrically operated fan, at the tunnel mouth which sucked the foul air out through a ventilation pipe at 4000 cubic ft a minute. The foul air was replaced by a draft of fresh air, enabling work to continue at the face.

At 8pm on Saturday evening, shift work finished as usual until Sunday at midnight. The electric fan was turned off and the pump at the face was turned on. This ran until 5pm on Sunday afternoon, when a problem occurred and the engine stopped. As there was no ventilation the tunnel began to fill with deadly carbon monoxide and dioxide gas.

This caused little concern, however, as work was not due to begin at the tunnel until Sunday midnight, and the electric fan was due back on at 7pm on Saturday, to suck out the deadly fumes. The fan did start as expected but stopped 40 minutes later due to a breakdown at the Arapeti sub-station. The scene was set for tragedy.

At 8pm on Saturday, Bernard Butler of Shannon, relieved the pump attendant. He had changed shifts so that he could spend Monday in Shannon with his parents. The attendant told Butler that the fumes were very thick in the tunnel and ‘a man would not last five minutes in it’. At 9.50 pm the foreman of the shift to start at midnight, Alfred E Maxwell, came to the tunnel to make his customary preliminary inspection. On the way, he stopped to chat with Arthur C Trigg at the sub-station. He informed Maxwell of the power failure, but Maxwell continued up to the tunnel.

Sometime later, Trigg, who was aware that both Butler and Maxwell had gone to the tunnel, became concerned as neither man had returned. At 10.40 pm he went to the tunnel mouth and met three tunnellers of the midnight shift, brothers Frank and Philip Graham and William Birss, and told them of his fears.

Trigg should not have left his post at the sub-station and the tunnellers said that he better go back in case the power came back on. The three tunnellers went 20 chains into the tunnel. They called out and banged on the pipes, but there was no reply. The fumes were overpowering. As they were not certain that Butler and Maxwell had entered the tunnel, they returned to the camp to see if they could find them. As the search proved fruitless, the terrible alternative dawned - they must be still in the tunnel.

Knowing full well the dangers, the three men set off to rescue their mates. As they were putting on their gumboots at the tunnel mouth they were joined by 28 year old William Robert Miller, assistant engineer. Miller wanted to go in alone, but before he could rush in, Frederick Birss arrived, father of William Birss. They decided to all enter the tunnel.

They entered the tunnel at 11.20 pm. Trigg remained at the sub-station, hoping for the power to be restored and anxious for the safety of the men. At midnight when he was relieved he ran to the tunnel and entered it alone. He re-appeared sickened at his discovery and gasping from the fumes. ‘They are down’, he shouted. ‘Raise the camp’, and fell unconscious. Before the relief attendant had aroused the men in the camp, Trigg recovered and gallantly ran back into the tunnel. He was picked up later by a rescue party - alive, but in a bad way.

The news of the disaster spread like wildfire through the works and men rushed to help. The fumes were very dense, and only the most experienced men were chosen to carry out the rescue. Two separate rescue parties were formed. The first had a terrible ordeal, having been affected by the fumes, and some of its members were rescued by the second party. The bodies of four of the victims were found about 20 chains from the entrance and brought out on trucks. At 1.45 am the electric fan was restarted and at 2.10 am the third rescue party went in. They found Philip Graham, and three chains further in, the bodies of Maxwell and Butler.

The only man who appeared to show signs of life after the rescue attempt was Frederick Birss, but although artificial respiration was tried for an hour and a half on all the men, it was too late. Seven good men had been taken by the fumes.

The official inquiry held in Shannon a week later, ruled that the disaster was caused by a chain of tragic circumstances and nobody was to blame. The inquiry did note, however, that the heroism and gallantry shown on that fateful Sunday night, was of the highest order.